CD 1 (74:44) | ||

| Pathé, Paris, 1927-1928 | ||

| 1. | DER FREISCHÜTZ: Wie nahte mir der Schlummer (Comment trouver le calme) (Weber) | 6:34 |

| January 1927; (N200607/8) X.0612 | ||

| 2. | TANNHÄUSER: Dich, teure Halle (Salut à toi, noble demeure) (Wagner) | 3:06 |

| 22 June 1928; (201242) 7140 | ||

| 3. | FAUST: Il était un roi de Thulé (Gounod) | 3:37 |

| 22 June 1928; (unpublished take transferred from test pressing without matrix number) | ||

| 4. | FAUST: Il était un roi de Thulé (Gounod) | 3:22 |

| 22 June 1928; (201243) 7140 | ||

| Odéon, Paris, 1929-1930 | ||

| 5. | TOSCA: Non la sospiri la nostra casetta (Notre doux nid caché dans la verdure) (Puccini) | 3:06 |

| 12 May 1930; (Ki 3246-2) 188720 | ||

| 6. | TOSCA: Vissi d’arte (D’art et d’amour) (Puccini) | 3:15 |

| 12 May 1930; (Ki 3245-2) 188720 | ||

| 7. | SIGURD: Salut, splendeur du jour (Reyer) | 6:21 |

| 16 May 1930; (Ki 3265/6) 188724 | ||

| 8. | LOHENGRIN: Einsam in trüben Tagen (Seule dans ma misère) (Wagner) | 4:13 |

| 25 January 1929; (XXP 6814) 123613 | ||

| 9. | TANNHÄUSER: Dich, teure Halle (Salut à toi, noble demeure) (Wagner) | 3:50 |

| 25 January 1929; (XXP 6815) 123613 | ||

| 10. | TRISTAN UND ISOLDE: Mild und leise, wie er lächelt (Doux et calme) [Liebestod] (Wagner) | 5:49 |

| Date unknown; (Ki 2821-3, Ki 2822-2) 188696* | ||

| 11. | DIE WALKÜRE: Ein Greis in grauen Gewand (Drapé dans une cape noire) (Wagner) | 3:53 |

| 17 May 1929; (XXP 6887-2) unpublished | ||

| 12. | DIE WALKÜRE: Ein Greis in grauen Gewand (Drapé dans une cape noire) (Wagner) | 4:05 |

| 4 February 1930; (XXP 7024-1) 123684 | ||

| 13. | DIE WALKÜRE: Siegmund heiss‘ich (Siegmund suis-je) (Wagner) | 3:47 |

| with René Verdière, tenor4 February 1930; (XXP 7023-2) 123683 | ||

| 14. | SIEGFRIED: Ewig war ich (Dès l’origine jusqu’à cette heure) (Wagner) | 4:27 |

| 4 February 1930; (XXP 7025-2) 123684 | ||

| 15. | GÖTTERDÄMMERUNG: Starke Scheite schichtet mir dort (Qu‘un bûcher s‘élève là-bas) [Brünnhilde’s Immolation] (Wagner) | 15:18 |

| 19 March 1929; (XXP 6853/6854) 123634 25 March 1929; (XXP 6862/6863) 123635 | ||

CD 2 (67:49) | ||

| Odéon, Paris, 1929-1930 (continued) | ||

| 1. | Mein gläubiges Herze (Mon âme croyante tressaille et chante) from Cantata No. 68, BWV 68 (Bach) | 3:41 |

| 15 April 1929; (XXP 6872) 123641 | ||

| 2. | Tristesse, based on Étude, Op. 10, No. 3 (Chopin, arr. Litvinne) | 3:56 |

| 15 April 1929; (XXP 6871) 123641 | ||

| Columbia, Paris, 1938 | ||

| 3. | TRISTAN UND ISOLDE: Mild und leise, wie er lächelt (Doux et calme) [Liebestod] (Wagner) | 6:51 |

| 1 June 1938; (CLX 2031-1, CLX 2032-2) unpublished | ||

| 4. | TRISTAN UND ISOLDE: Mild und leise, wie er lächelt [Liebestod] (Wagner) | 6:48 |

| 1 June 1938; (CLX 2033-1, CLX 2034-1) issued on HMB179 | ||

| Pathé, Paris, 1939 | ||

| 5. | Der Erlkönig, D. 328 (Schubert) | 4:14 |

| (PARTX 1350-3) issued as a dubbing on a private 78 rpm disc | ||

| 6. | Liebeslied, Op. 51, No. 5 (Schumann) | 2:43 |

| (PARTX 1351-2) issued as a dubbing on a private 78 rpm disc | ||

| 7. | Lied der Suleika, Op. 25, No. 9 (Schumann) | 1:49 |

| (PARTX 1351-2) issued as a dubbing on a private 78 rpm disc | ||

| Pathé-Marconi, Paris | ||

| 8. | Verborgenheit, No. 12 from Mörike-Lieder (Mörike, Wolf) | 2:51 |

| 24 May 1944; (OLA 4301-1) unpublished on 78 rpm | ||

| 9. | Per valli, per boschi (Blangini) | 1:55 |

| with Gérard Souzay, baritone24 May 1944; (OLA 4302-1) issued on HMA94 | ||

| 10. | Signes (Leguerney) | 3:16 |

| with Gérard Souzay, baritone24 May 1944; (OLA 4303-1) issued on HMA94 | ||

| 11. | Sylvie, Op. 6, No. 3 (Choudens, Fauré) | 2:20 |

| 25 May 1944; (OLA 4304-1) issued on HMA71 | ||

| 12. | Au bord de l’eau, Op. 8, No. 1 (Sully Prudhomme, Fauré) | 1:54 |

| 25 May 1944; (OLA 4305-1) issued on HMA71 | ||

| French Radio | ||

| Recorded 5 June 1954, broadcast 9 August 1954 | ||

| 13. | Vergine Tutto Amore (Durante) | 3:24 |

| 14. | Beau soir (Bourget, Debussy) | 2:16 |

| 15. | Je tremble en voyant ton visage, No. 3 from Le promenoir des deux amants (Tristan L’Hermite, Debussy) | 1:51 |

| 16. | Nun wandre, Maria, No. 3, from Spanisches Liederbuch (Wolf) | 3:01 |

| 17. | Um Mitternacht, No. 19, from Mörike-Lieder (Mörike, Wolf) | 3:21 |

Appendix | ||

| Lucienne de Méo | ||

| Complete Commercial Recordings | ||

| French Columbia, 1928 | ||

| 18. | ALCESTE: Divinités du Styx (Gluck) | 3:59 |

| 25 February 1928; (WLX247-1) D14212 | ||

| 19. | DER FREISCHÜTZ: Und ob die Wolke (En vain au ciel) (Weber) | 3:45 |

| 25 February 1928; (WLX246-1) D14212 | ||

| 20. | DIE WALKÜRE: Der männer Sippe (Tous nos parents, groupés autour de nous) (Wagner) | 3:52 |

| 14 April 1928; (WLX 351-2) unpublished on 78 rpm | ||

*Note: The recording date of this selection is uncertain. The surviving recording sheets for these matrices do not list a recording date for the published takes 3 and 2 respectively. The date of 19 December is listed for takes 1 and 2 for part 1, and take 1 for part 2. The published takes were most likely recorded during a later session.

Languages: | ||

Producers: Scott Kessler and Ward Marston

Audio Conservation: Ward Marston and J. Richard Harris

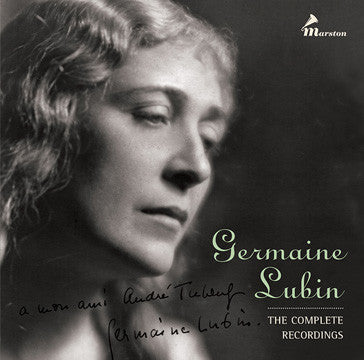

Photographs: André Tubeuf

Booklet Design: Takeshi Takahashi

Booklet Notes: Vincent Giroud and André Tubeuf

Marston would like to thank Luc Bourrousse, Elizabeth Black, and Robert Tuggle for editorial advice.

Marston would like to thank Lawrence F. Holdridge and André Tubeuf for providing unique test pressings.

Marston would like to thank Michael H. Gray, David Mason, and Christian Zwarg for providing important discographic information.

Marston is grateful to the Estate of John Stratton (Stephen Clarke, Executor) for its continuing support.

GERMAINE LUBIN

(Paris, 1890 – Paris, 1979)

“I lived for my art, and politics never interested me,” Germaine Lubin told Lanfranco Rasponi in 1978. Yet perhaps no singer better exemplifies the ties that have always existed in France between opera—and, indeed, culture in general—and politics.

Born in Paris on 1 February 1890, Lubin had an exotic ancestry, which included Polish and Berber blood, and spent her early childhood in French Guiana, where her father, a medical doctor, was posted. On her mother’s side, she was descended from Léonard Nicolas Boegert, an Alsatian who, under the name Beker, became chief of staff to Marshal Masséna under Napoleon and was made a count. First trained as a pianist, the young Germaine turned her interest to singing when she heard the great contralto Suzanne Brohly, who sang at the Opéra-Comique from 1906 onward. After studying privately for a year with Martini, in 1908 she entered his singing class at the Conservatoire, where she was also coached by the baritone Jacques Isnardon and was noticed by Gabriel Fauré, who since 1905 had directed the institution. At the 1910 competition, she obtained only honorable mentions. “Mlle Lubin possesses a striking physique and voice,” Reynaldo Hahn wrote in Le Journal; “however, such a gifted young woman will have to work hard and, especially, give some thought to the difficulties and significance of singing—and how vain it is when deprived of mystery.” The following year, she got a second prize in opera and an honorable mention in opéra-comique. Finally, in 1912, she triumphed with three first prizes in singing, opera, and opéra-comique, singing arias from Oberon, Faust, and La Navarraise. Hahn, this time, commented on her radiance and vocal splendor as Rezia, regretting only that her middle and lower registers were still a little weak. He enjoyed her even more as Anita and thought her Marguerite would have been “almost ideal” if she had sung less loudly at times. Several theaters courted her at once, including the Théâtre de la Monnaie in Brussels. Announced on 15 July, her hiring by the Opéra had to be disclaimed once it was revealed she had already signed a contract with Albert Carré at the Opéra-Comique, where she made a highly successful debut on 13 November as Antonia in Les contes d’Hoffmann. During the next two seasons, she appeared as Bacchis in Erlanger’s Aphrodite, Toinette in Xavier Leroux’s Le chemineau, Camille in Zampa (with Daniel Vigneau in the title-role), and Francesca in Franco Leoni’s Francesca da Rimini, first heard in January 1914 in a double bill with Falla’s La vida breve. In Guy Ropartz’s Le pays, which received its Opéra-Comique premiere on 17 April 1913, she sang the difficult part of Koethe, opposite Thomas Salignac as Tual. “The voice is superb, the diction is impeccable, the temperament is powerfully dramatic,” wrote Edmond Stoullig in Les annales du théâtre et de la musique. According to her biographer Nicole Casanova, Lubin got on well with her Salle Favart colleagues, with the exception of Marthe Chenal, who sang the title-role in Aphrodite, and Geneviève Vix, whom she succeeded as Leoni’s Francesca. Meanwhile she continued taking vocal lessons from Félia Litvinne, whom she had greatly admired ever since she had heard her as Alceste. She credited her teacher, who continued to coach her over the next ten years, with her remarkable ability to sing softly in the upper register.

In 1913, Lubin married the popular poet and playwright Paul Le Fèvre, in literature Paul Géraldy (1885–1983), whose 1913 verse collection Toi et moi was evidently, at least in part, inspired by her. The following year, when Carré stepped down as Opéra-Comique director, she agreed to join the Opéra, now headed by Jacques Rouché, but with the outbreak of war the house closed. Once it reopened, Lubin appeared in January 1916, under Camille Chevillard, in the second scene of Vincent d’Indy’s 1883 “dramatic legend” Le chant de la cloche, which had been staged for the first time in Brussels in 1912. During her first Opéra season, Lubin sang her first Marguerite, and while she was praised for her portrayal of the role, she never felt completely comfortable with it. That same year she gave birth to a son, Claude. In 1917 she sang Dolorès in one of the last revivals of Paladihle’s Patrie!, Juliette in Roméo et Juliette (opposite John O’Sullivan and Louis Lestelly), Aida (the only Verdi role she ever undertook), and Fausta in the final two performances of Massenet’s Roma at the Opéra, with Ketty Lapeyrette, Léon Laffitte, Francisque Delmas, Jean Noté, and André Gresse. She also appeared once, taking over from Marthe Chenal, in the title role in the unsuccessful local premiere of Raymond Roze’s Jeanne d’Arc, originally staged at Covent Garden in 1913; the cast included the tenor Paul Franz, who remained one of her favorite partners, and Delmas. In 1918, she sang her first Thaïs and took part, as Télaïre, in the first modern Opéra revival of Rameau’s Castor et Pollux with Aline Vallandri (Phoebé), Rodolphe Plamondon (Castor), Louis Lestelly (Pollux), and Léon Gresse as Jupiter, with Alfred Bachelet conducting. In 1919 she also returned to the Opéra-Comique, where Carré was again at the helm, and sang Antonia, Louise, and her first Paris Tosca, as well as Fauré’s Pénélope for its first Salle Favart staging. At the Opéra she sang Berlioz’s Marguerite, with Franz and Gresse, her first Salammbô in Reyer’s opera, and Blanche at the Paris premiere of Max d’Ollone’s Le retour, first staged at Angers in 1913; it disappeared after three performances, of which she only sang the first two. She appeared at Nantes as Thaïs, Tosca, and Gounod’s Marguerite, and made her Monte Carlo debut as Thaïs and Tosca, with Beniamino Gigli and Mattia Battistini, under Victor De Sabata. It was around that time that she auditioned for Jean de Reszke, who advised her that her future was as a dramatic, not lyric, soprano.

In June 1920, at the Opéra, Lubin premiered the part of Nicéa (“Queen of Pleasure”), alternating in the role with Jeanne Hatto, in d’Indy’s La légende de saint Christophe. The cast included Franz in the title-role, Delmas, Albert Huberty, and Édouard Rouard in the openly antisemitic part of “Le roi de l’or.” That same year, she sang her first Wagner role, Sieglinde, when a revival of Die Walküre, under Chevillard, put an end to the wartime ban on the composer’s work; in the cast were Marcelle Demougeot (Brünnhilde), Lapeyrette (Fricka), Franz (Siegmund), Delmas (Wotan), and Gresse (Hunding). In 1922 Lubin sang the title-role in Henry Février’s Monna Vanna (premiered with Lucienne Bréval, Muratore, and Vanni-Marcoux in 1909) with Sullivan as Prinzivalle and Huberty as Guido, and appeared as Marina in the Palais Garnier’s first French-language Boris, with Vanni-Marcoux in the title-role, Huberty as Pimen, Gresse as Varlaam, and Lapeyrette as the Innkeeper; Serge Koussevitzky conducted. In the same year she sang in the Opéra premiere of Henri Rabaud’s La fille de Roland, first staged at the Opéra-Comique in 1904; Franz and Delmas were in the cast.

Mortified to be passed over in favor of Fanny Heldy when Lohengrin was revived in Paris in 1922, Lubin took her revenge by making her role debut in German the following year, in Vienna, under Clemens Kraus. In Paris, she sang her first Eva in Die Meistersinger, a part created there in 1897 by Bréval, like Lubin a dramatic soprano. Franz was Walther, Delmas Sachs, and Robert Couzinou Beckmesser. Though she sang it again in 1930, this time with Journet as Sachs, she did not think it was one of her best roles and judged Yvonne Gall superior in it. She was apparently considered for the first Paris Turandot, though the part went to Maryse Beaujon instead.

In 1924, Lubin returned to Vienna, this time to sing Ariadne, under the composer, with Karl Aagaard Østvig as Bacchus, and give a song recital. In 1925, she sang her first Tannhäuser Elisabeth, opposite Franz, and in 1926 her first Agathe in Der Freischütz, with René Verdière as Max and Huberty as Kaspar, as well as her first Alceste, with Georges Thill as Admète. “As for Mme Germaine Lubin, the new Alceste,” Henri de Curzon wrote in La Nouvelle Revue, “she gave us a complete and profound impression of artistic joy, the like of which would be difficult to find today. […] To her imperial physical beauty and noble gestures, she added an ample and pure voice, with gripping accents of sincerity, unaffected pathos, light and luminous sonorities, in turn vibrant and delicate, which were a constant charm, as was her unfailingly truthful acting.”

Long scheduled to premiere the part of Octavian in France, with Strauss and Hoffmannsthal both in support, Lubin had studied the part with its original creator in Dresden, Marie Gutheil-Schoder. She first sang it at Monte Carlo in 1926, with Gabrielle Ritter-Ciampi (a singer she greatly admired) as the Marschallin, under De Sabata. She repeated the role the following year for the work’s first Paris staging (supervised by Gutheil-Schoder), with Jeanne Campredon as the Marschallin, Jeanne Laval as Sophie, and Huberty as Ochs. Lubin was by then separated from her husband, and was having an affair with one of the heads of the publisher Larousse, a married man whose wife refused to grant him a divorce. A daughter, Dominique, was born in 1929 and was given her mother’s name. Lubin herself eventually moved to a spacious apartment overlooking the river on Quai Voltaire, where she lived, with a postwar interruption, until the end of her life.

In 1928, Lubin switched roles in Die Walküre, singing her first Brünnhilde to Lotte Lehmann’s Sieglinde, with Wilhelm Furtwängler conducting. Also at the Opéra, she sang the role in Siegfried, with Joachim Sattler in the title-role and Hans Hotter as Wotan. The following year, she appeared as Cassandre in a rare revival of Berlioz’s La prise de Troie. (Les Troyens à Carthage, with Marisa Ferrer as Didon, was given on a separate evening.)

In 1930, Lubin sang her first Leonore in Fidelio, under Bruno Walter, as well as her long-awaited Paris Isolde (first essayed at Nantes), under Philippe Gaubert, with Franz as Tristan. It was followed, two years later, by her first Kundry, with Lauritz Melchior as Parsifal and J. Grommen as Gurnemanz. “One of the best Kundrys one has ever been able to hear and, for once, see,” wrote Hahn when she repeated the role in 1935. On 27 June 1931 she gave a single performance of Gluck’s Iphigénie en Tauride, conducted by Pierre Monteux, with Martial Singher as Oreste and José de Trévi as Pylade; a rival cast (Balguerie, Gaston Micheletti, Louis Musy) could be heard in the same season at the Opéra-Comique under Albert Wolff. Lubin had first sung the role in Amsterdam the previous year. At the 1931 Salzburg Festival, she appeared on 3 and 22 August, under Bruno Walter as Donna Anna, a role she had studied in 1924, in the same city, with Lilli Lehmann (“terrible! méchante!” she later recalled), headed by Karl Hammes in the title-role.

In January 1932, Lubin was Empress Charlotte at the world premiere of Darius Milhaud’s Maximilien, with André Pernet in the title-role; the cast included Marisa Ferrer, José de Trévi, Arthur Endrèze, and Martial Singher, with François Ruhlmann conducting. The following month, after studying choreography with Serge Lifar for a full six months to do her own dance at the end (as she proudly told the present writer in 1974), she appeared as Elektra in the Paris premiere of Strauss’s opera, conducted by Gaubert. The Chrysothemis was “the other Germaine,” Germaine Hoerner, while Lapeyrette sang Klytemnaestra and Singher Oreste. “Nobody expected such a tour de force,” Constantin Photiadès wrote in the Revue de Paris, who only regretted that Lubin’s words were not clearer. “The role of Elektra, so heavy, so treacherous, is taken well in her stride. She sings, acts, mimes, dances it with absolute mastery and even ease. Madame Germaine Lubin is very close to perfection.” She considered Elektra one of the high points in her career and her name long remained associated with the role in Paris.

In 1933, Lubin added one final role to her extensive Wagner repertory with the Götterdämmerung Brünnhilde, which she sang alongside Hoerner as Gutrune, Lapeyrette as Waltraute, Franz as Siegfried, Singher as Gunther, and Journet as Hagen, Gaubert conducting. She was Elsa on 25 February when Marjorie Lawrence made her house debut as Ortrud. In her 1949 autobiography, the Australian soprano (while claiming Lubin had been one of her heroines in her student days) reports that her own show-stopping rendering of “Entweihte Götter” infuriated her rival. “Moi?—jalouse d’elle?” was Lubin’s characteristic denial to a postwar interviewer. From then on Lawrence often covered Lubin’s roles when she was indisposed, but the two seldom appeared together again.

The following year, 1934, Lubin sang her first Paris Donna Anna. As in Salzburg, the conductor was Bruno Walter; the cast included Ritter-Ciampi as Elvira, Solange Delmas as Zerlina, André Pernet as Don Giovanni, Miguel Villabella as Ottavio, Paul Cabanel as Leporello, and Henry Medus as the Commendatore. “Throughout, she brings to it a profound feeling,” Hahn wrote in Le Figaro, “and in the perilous Act 2 aria, she mixes pathos and technique with uncommon virtuosity. It is a feat very few singers can accomplish so felicitously.” Once again walking in the footsteps of Bréval, she sang Vita in d’Indy’s L’étranger, with Pernet in the title role. (She had already sung extracts in concert in 1929 to mark the composer’s 78th birthday.) It was the last revival of the work, which had not been heard at the Opéra since 1917.

In 1935, Lubin participated in a Fauré festival at the Opéra by singing Act 2 of Pénélope, with de Trévi as Ulysse and Singher as Eumée. A few weeks before the death of Paul Dukas, she also was the first Paris Opéra Ariane in his Ariane et Barbe-Bleue (originally staged at the Opéra-Comique in 1907), with Lapeyrette as the Nurse and Etcheverry as Barbe-Bleue, under Gaubert. At the Maggio musicale in Florence, she appeared as Télaïre in Castor et Pollux. In 1936, she repeated her Isolde, under Paray, with de Trévi as Tristan, Endrèze as Kurwenal, and Marjorie Lawrence as Brangäne, and her Alceste, with Jouatte and Singher. She also sang Elsa with the Opéra troupe at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées while the Palais Garnier was being restored, with Thill in the title-role, Renée Gilly as Ortrud, Singher as Telramund, under Gaubert. In 1937, with the same conductor, she repeated her Leonore in Fidelio, with Georges Jouatte, Lotte Schoene, Georges Noré, and José Beckmans. In February and April 1937, she sang the title-role in a single revival of Massenet’s Ariane, marking the reopening of the Palais Garnier, with Thill, Ferrer, and Singher, under Paul Paray. Lubin, who told an interviewer she considered Massenet more difficult to sing than Wagner, had carefully prepared her role with Hahn. The same year, she appeared at Covent Garden as part of the Coronation festivities in Dukas’s Ariane et Barbe-Bleue, with the same cast as in 1935. The critic of the Musical Times, who did not care for the work, conceded that Lubin, “by her impersonation, at once stately and sensitive, and her calm, competent, shapely singing, […] was the rare type of artist for whom such a part was conceived.” In London, she also appeared as Alceste, with Jouatte; Francis Toye praised her as “well-nigh the ideal Alceste.” During that summer she sang Isolde at Vichy, under Karl Elmendorff.

Reyer’s Salammbô had its last major Opéra revival in 1938, conducted by Ruhlmann, with José Luccioni, Jouatte, Beckmans, and Pernet. Hahn, while regretting that Reyer had conceived the part of Flaubert’s young heroine for a dramatic soprano, praised Lubin as its greatest exponent since its creator Rose Caron. “This soprano’s voice is perhaps not all that it used to be,” wrote Herbert F. Peyser in the New York Times, “and it is possible to pick flaws in her singing (though she not infrequently surprises by the beauty and the eloquence of what she does). But she is the mistress of the grand style, such as this music exacts, and in presence, in bearing, in beauty of gesture, in all that comes under the head of ‘plastique,’ she belongs to an older and a better age.” She was to sing the part again at its final revival in 1943.

On 20 February 1938, Lubin made her Berlin debut as Sieglinde, under Heinz Tietjen, with Franz Völker as Siegmund. Her success (Hermann Goering was in the audience and congratulated her after the performance) prompted an invitation to Bayreuth to appear as Kundry the following summer. Contrary to what is occasionally reported, she was not the first Frenchwoman to sing at the festival, where Marcelle Bunlet had preceded her in the same role in 1931. This 1938 Parsifal was conducted by Franz von Hoesslin, in a production designed by the young Wieland Wagner. The title-role was sung by Fritz Wolff, replacing Franz Völker, who had injured himself, and Jaro Prohaska was Amfortas. In her postwar memoir, Friedelind Wagner, known as Mausi, who was by then alienated from her family and whose testimony should therefore be treated with circumspection, claims, without being more specific, that Tietjen had invited Lubin for “political reasons” and thought she was not “up to Bayreuth standards.” Friedelind adds that the presence of Lubin’s handsome black chauffeur Clément, though cleared with the mayor of the city, caused a furore with the “Hitler Maidens,” but that Lubin herself, “tall, elegant, blond, looking like a Roman madonna,” was paid “marked attentions” by Hitler, to the right of whom she found herself seated at dinner at Wahnfried, with Goebbels at the same table. A photograph taken during the after dinner drinks shows her with the Führer, who sent her flowers and an inscribed photograph the following day.

Back in Paris, Lubin appeared as Isolde under Furtwängler. Peyser, who found little to enjoy in the orchestral playing and (with the exception of Herbert Janssen’s Kurwenal) the singing of the rest of the cast, was once again, enthusiastic: “In many ways it is not hard to understand why Bayreuth has taken Germaine Lubin to its bosom. Her Isolde, sung in flawless German and with a sense of the Wagnerian style wholly different from the Gallic misconception, is above all a beautiful externalization. I do not always feel in it passion, fire, or an absolute spontaneity of inner conviction. But some of its expressions ring affectingly true and while, here too, there are vocal flaws, certain passages and certain details are remarkable. I have rarely, for instance, heard the last F-sharp of the “Liebestod” delivered with such a transfigured beauty of tone and such another worldly quality of utterance. And not in years have I seen an Isolde who in the “Liebesklage” enacted her grief with such piteous beauty of pose and movement. And at all times this was an Isolde who wooed the eye.” Peyser was equally thrilled with her “utterly magnificent” Paris Alceste in October of the same year; he described her as “an artist who, in her sovereign command of the grand manner, in splendor of tragic expression and in majestic grace of plastique, is an incontestable continuator of the line of Lilli Lehmann, Milka Ternina, and Olive Fremstad.”

In early 1939, Lubin sang the Siegfried Brünnhilde in Paris (in German, for once), under Furtwängler. “How well might her German associates,” wrote Peyser in the New York Times, evidently referring to Hans Hotter’s Wotan and Sattler’s Siegfried, “obtain from her pointers about the true Wagner style! Not since Olive Fremstad have I witnessed so nobly beautiful a performance of the awakening pantomime or of the greeting to sun and earth. […] She sang superbly, moreover, and, contrary to the vicious tradition which is becoming more and more ingrained, boldly dared the gleaming high C at the close.” In March, Lubin took part in the world premiere of Henri Sauguet’s La chartreuse de Parme at the Opéra, along with Raoul Jobin (Fabrice), Endrèze (Comte Mosca), Huberty (Fabio Conti), and Courtin (Clélia). Sauguet, whose autobiography contains a lively account of the difficult circumstances of the work’s genesis, had wanted Lubin from the start, but was told that “la sublime” did not like appearing in modern works (“You’ll never get her”). Once she had been persuaded to look at the score, she threatened to withdraw unless the composer raised the mezzo-soprano tessitura and added high notes, and she was annoyed once she realized Clélia had a longer role. Yet Sauguet found her performance “superb.” Hahn, who disliked the work, as did Peyser, found her ill-suited to it, while admitting she was “as always, interesting and dignified.” In the same month Lubin and Endrèze took part, under Hahn, in the first performance of the final tableau from Gounod’s unfinished opera, Maître Pierre.

In the spring, Lubin was reinvited to Berlin to sing Kundry, Sieglinde, and Strauss’s Ariadne (with the composer conducting). She sang Isolde at Covent Garden in May, under Beecham, to Melchior’s Tristan. In June she sang Sieglinde to Flagstad’s Brünnhilde in Zurich, under Furtwängler. While complaining about the conductor’s erratic tempi, Peyser wrote in the New York Times: “What gave the representation its distinction was the superb dual achievement of Miss Flagstad’s Bruennhilde and Germaine Lubin’s Sieglinde. It was, in truth, an exceptional privilege to hear these two artists in conjunction, to note how happily the one complements the other, to contrast the clear, cold voice and effortless production of the Norwegian with the rapturous and warmly beautiful if less consummately schooled tones of the Parisian soprano. […] Miss Lubin […] is one of the most moving and plastically beautiful Sieglindes of my experience. These two sovereign interpretations completely carried away the audience.”

In the summer of 1939, having first cleared the matter with the French ministry of Foreign Affairs, Lubin returned to Bayreuth, this time as Isolde, under De Sabata. The rest of the cast included Max Lorenz—her Zurich Siegmund—as Tristan, Margarete Klose as Brangäne, Prohaska as Kurwenal, and Josef von Manowarda as Marke. Once again, Hitler was in attendance, and he came backstage to congratulate the singer, who, in turn, spoke ill-advisedly to the German press about her delight in meeting the German leader. The declaration of war on 3 September forced her to cancel the final Tristan performance.

With appearances in Vienna, Salzburg, London, Bayreuth, Florence, and Monte Carlo (Kutsch and Riemens also mention Prague, but do not specify in which work), Lubin’s career had been confined to Europe. She was not part of the Opéra’s visit to Buenos Aires in 1936, during which Lawrence sang both Télaïre and Kundry. As late as May 1940, before the invasion of Belgium, she was able to travel to Bucharest to sing Fidelio (in French). Though she was entering the last phase of her career, the war no doubt prevented her from being heard in New York. The New York Times of 22 August 1939 reported that the Met was negotiating with Lubin, suggesting she might appear as Sieglinde, Brünnhilde, or Isolde, or even as Dukas’s Ariane. Negotiations were reopened the following year with Lubin receiving a contract to sing Alceste scheduled for January 1941, but Lubin’s request for a passport was denied by the Nazi authorities and the production went to Rose Bampton instead. The war also torpedoed such projects as Paris Opéra stagings of Arabella and even Friedenstag with Lubin.

Like the enormous majority of the French population at the time, Lubin saw nothing wrong with the regime that was put in place at Vichy in the summer of 1940. Marshal Pétain was a longtime admirer of hers, having even courted her favors when they met during the First World War (another admirer was the future Marshal de Lattre de Tassigny, who defected to the Gaullist forces in 1942); only a year before Pétain had entertained her in Spain, where he was the first French ambassador to Franco’s regime, when she gave recitals in Madrid and Barcelona, along with Charles Panzéra. Though, as a French national, she was no doubt deeply affected from the humiliating defeat suffered by her country, she was openly Germanophile and all the more readily resumed work at the Opéra since, under Rouché’s cautious management, it was officially urged to invite German musicians, some of whom were longtime acquaintances, while German works, of which she was the foremost French interpreter, were prominently programmed. Though she never had any contact with Hitler after the summer of 1939, he personally intervened to have her son Claude, a war prisoner, freed in 1940. She herself occasionally appealed on behalf of prisoners and persecuted Jews to Winifred Wagner, who recommended to her a captain named Hans Joachim Lange: posted in Paris, he helped with her requests, taking personal risks to the point of eventually running afoul of the Gestapo. “It was my way of serving my country at that particular moment,” she later declared. “Nobody knows how many prisoners I had released.”

When the Opéra reopened in the fall of 1940, Lubin made her rentrée as Leonore, with Jouatte as Florestan and Beckmans as Pizarro, and subsequently sang Télaïre, with Hoerner as Phoebé, Jouatte as Castor, and Endrèze as Pollux, and repeated her highly successful Alceste. In February 1941, under Gaubert (who died a few months later), she sang her first Marschallin to considerable acclaim, with Courtin as Octavian, Jeanine Micheau as Sophie, and Huberty as Ochs, while the veteran Lapeyrette appeared as Annina. In May 1941, she sang Isolde, in German, at the Opéra with the visiting Berlin Staatsoper, conducted by Herbert von Karajan, with Lorenz as Tristan. In June 1942, at the personal insistence of Pierre Bessand-Massenet, the composer’s grandson, she sang Charlotte to Jouatte’s Werther at the Opéra-Comique, under d’Ollone, as part of the Massenet centenary celebrations. In the same theater, she appeared as Ariadne, with Jouatte as Bacchus, in the Paris premiere of Strauss’s opera, an event presented for propaganda purposes as part of Franco-German cultural collaboration.

Beyond such appearances, some of which were in front of Nazi soldiers in uniform, for whom the theater had been requisitioned, there is no evidence that Lubin behaved shamefully during the war, unlike countless ordinary Frenchmen and women who routinely, and with total impunity then or since, denounced their Jewish next-door neighbors and sent them to their deaths. Despite several invitations (notably from Bayreuth), she wisely refrained from accepting engagements in the Reich, singing only Isolde at Zurich, in neutral Switzerland, in June 1941. If she gave a recital in 1942, accompanied by Wilhelm Kempf and Alfred Cortot, on the occasion of the exhibition of sculptures by Arno Breker, it was, she claimed, to secure the liberation of Maurice Franck, the Jewish chef de chant at the Opéra, whose release she subsequently had to obtain by appealing directly to Otto Abetz, the Nazi ambassador. But the fact remained that she had access to such figures, and it was bound to come back to haunt her at the Liberation.

On 13 August 1944, Lubin sang Alceste in a semi-staged version at the Sorbonne. Two weeks later, she was briefly arrested by members of the French liberation forces. In early September, she was arrested a second time, presumably after being denounced by Opéra colleagues (Hoerner reportedly made no secret of her satisfaction). First sent to the transit camp of Drancy, outside Paris, she was briefly imprisoned at Fresnes and freed in early November, after the head of the Figaro had appealed to the chief of staff of General Eisenhower.

Lubin was not the only victim of the purges conducted at the behest of the self-appointed comité d’épuration at the Opéra: Micheau and Ferrer were both banned from performing for brief periods, and Rouché himself, then eighty-three, was fired. But she paid the heaviest price, and the main explanation why she did can only be the position she had reached thanks to her celebrity. Most of the accusations against her—being godmother to Goering’s children, or Ribbentrop’s mistress, giving Hitler a tour of the Opéra, sporting a diamond swastika brooch presented to her by the Führer, etc.—were totally fanciful, though not unusual in the climate of the period, when millions of French people who had been held in subjection by German forces that never exceeded 40,000 suddenly discovered in themselves patriotic urges which had to find an outlet in scapegoating. Charged with “conspiracy against the state”—“Except for having eaten the flesh of children, there is nothing I was not accused of,” she bitterly told Rasponi—she was exonerated in early 1945, but charged again in April 1945, after being summarily dismissed from the Opéra troupe as of 1 January. Among the witnesses who defended her against mostly unsubstantiated accusations were, in addition to Maurice Franck, the Polish-born soprano Marya Freund and her son Doda Conrad, now serving in the US army. But the charge of having been visited by German officers in her château in Touraine precluded dismissal of the case. In May and June 1946 she was arrested again in Orléans and jailed for two weeks, this time over the arrest and deportation of her gardener, whom someone had denounced as a communist. Her cause was not helped by the publication of Friedelind Wagner’s memoir Heritage of Fire, in which the composer’s grand-daughter presented Lubin as a favorite of Hitler and emphasized her ties with the disgraced Wagner family. On 7 December 1946 Lubin was sentenced to lifelong “national indignity” and confiscation of her property, and banned from appearing in public in her lifetime. Partly thanks to the intervention of Géraldy, her ex-husband, the sentence was reduced to five years and the confiscation to one million francs. The stigma, however, remained. When Lubin, who had temporarily moved to Switzerland, was invited by the Geneva Opera to appear in Tannhaüser, the French embassy was instructed to pressure it into rescinding the offer. And when the Paris trial was resumed in 1949, the five-year condemnation was upheld.

Having nursed her voice with coaches in Milan, Lubin prepared her return to the concert hall, as she was able to move back into her Quai Voltaire apartment, “lent” in the meantime to a prominent Gaullist general. On 29 March 1950, she gave a triumphant comeback recital at the Salle Gaveau, singing mélodies by Fauré and Debussy and Lieder by Schumann and Hugo Wolf. In 1952 she appeared in Geneva and Zurich, and gave another recital in Paris on 19 June, before attending the Bayreuth Festival, which had reopened the previous year. Georges Enescu, a friend of many years, accompanied her at a private recital hosted that fall by the Queen of Greece. The suicide of her son, in January 1953, prompted her to end all public appearances. She devoted herself to teaching: singers who worked with her for short or long periods include Régine Crespin (who studied the Marschallin with her), Suzanne Sarrocca, Denise Duval, Denise Monteil, Jocelyne Taillon, Nadine Denize, and Rachel Yakar. Though friends from happier times—Karajan, for one—declined to resume acquaintance with her, others, such as Kempff, remained on close terms. In January 1966 she was interviewed by Max de Schauensee for Opera News. Disdainful of the current state of French singing (save for Crespin), the “tall, slightly bent woman, clutching a saffron scarf” proclaimed her admiration for Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and Renata Tebaldi. Until the very end of her life a familiar presence at Opéra premieres and the Aix-en-Provence festival, at once legendary and amazingly approachable and hospitable to admirers of the younger generation, she died in Paris on 17 October 1979.

Lubin did not like her recordings. “They’re all bad,” she would declare emphatically at the end of her life. Sadly, as a result, she made comparatively few. They reflect, alas, a small part of her extended, versatile repertory. The saddest loss of all maybe the 1939 Bayreuth Tristan, of which nothing is known to have survived. Hardly less distressing is the absence of her Alceste and Ariane, unanimously said to be two of her greatest assumptions—not to mention the other Ariane, the one by Massenet, in which she must have been incomparable. We have nothing from her four Strauss roles (Elektra, Ariadne, Octavian, the Marschallin); nothing from the many contemporary French operas in which she appeared: Ropartz’s Le pays, Milhaud’s Maximilien, Sauguet’s La chartreuse de Parme, among many others. And even though she recorded comparatively generous highlights of her Wagnerian repertory, we can only imagine what she may have sounded like as Kundry.

Particularly valuable are the early Pathé recordings of 1927-1928, as they allow us to hear the voice at its youthful best, since Lubin was thirty-seven to thirty-eight. Contemporary with the Agathe she sang at the Opéra, Leise, leise, for all Lubin’s denials of the quality of her records, actually conveys a fairly accurate picture of her voice: a clear, full soprano timbre, flexible and free and luminous at the top. Dich, teure Halle beautifully conveys Elizabeth’s impulsive, ardent nature; of her two readings, one may prefer the one from 1929, slightly more nuanced and with the “Salut à toi” at the end more neatly executed. The King of Thule song is remarkable both for the quality of her diction (with the word “charme” nicely emphasized) and the subtle shading of the expression. The final notes are even more delicately sung in the previously unpublished test pressing.

There is no evidence that Lubin ever appeared in Reyer’s Sigurd, unless she did so in the French provinces. When the opera was last revived in Paris in 1934, Marjorie Lawrence (and later Germaine Hoerner) sang Brunehild. However, Lubin has left a memorable account of the Awakening Scene in Act 2, worth setting aside the 1961 version by her pupil Crespin. Tosca she did sing, though not often. The two extracts confirm that she possessed a perfect voice for the part; even the hint of hauteur she brings to it seems appropriately stylish—as is the perfectly executed grace note in “Vissi d’arte.”

“Einsam in trüben Tagen” is everything one would wish for, both schwärmerisch (as required) and dignified, and with a ravishing diminuendo—specified in the score but hardly ever observed—on the A-flat at “mich heissen.” A reputed Sieglinde in her heyday, Lubin later claimed she felt no deep affinity with the role (as she told Raspoli in 1978, “she is a victim, and instinctively I have always disliked victims—and how right I was, as the future proved!”) She has nevertheless left an impressive account of “Die Männer sippe” (beginning at “ein Greis in grauen Gewand,”) in which her easy top shines. In “Siegmund heiss ich” we hear the excellent René Verdière (1899–1981), who appeared in The Walkyrie at the Opéra in 1927. As the Siegfried Brünnhilde, she displays a lovely trill on “heiter” and a gleaming high C at “Leuchtender der Spross!” Her Immolation Scene was recorded before she had actually sung the part on stage. The voice sounds almost light for the role at first, but she takes it well in her stride, and the high notes are firm and assured.

The aria from Bach’s “Also hat Gott die Welt geliebt” and the awful song based on Chopin’s Étude op. 10, no. 3 are reminders of how things were once done. In the latter, Lubin’s penchant for portamento—another remnant of another age—is particularly in evidence; and yet there is something winning about her grand manner and beauty of tone. The Bach, where she is stylistically at sea, even strident at times, makes for less happy listening.

Compared to the 1929 version, the two 1937 versions of the Liebestod show no indication of vocal decline, but perhaps a slight darkening of the timbre. Both are more involved dramatically, especially the one in German, when Lubin is liberated from Alfred Ernst’s awful French. It is all the more fortunate that Lubin was able to record Erlkönig and the two Schumann songs in French; hers are not immaculate readings, but sensitive and striking all the same.

Lubin’s 1944 recordings, made for Pathé-Marconi, just a few months before her life was to take a dramatic turn, betray no sense of impending drama. The two duets with the twenty-five-year-old Souzay, who lightens his voice to wonderful effect, are sheer delight, even if Lubin’s own voice, unflatteringly recorded, has perceptibly lost some of its sheen. The second side introduces us to the unfamiliar music of Jacques Leguerney (1906–1997), a pupil of Nadia Boulanger and friend of Poulenc, and best-known as a song composer. The two Faurés are sensitively, idiomatically rendered, but more impressive even is the Wolff, in which the texture of the voice comes through to great effect.

The broadcast from 1954 shows that Lubin, in her mid sixties, and despite a slight shortness of breath, still had some voice left. The two Debussy songs are sweetly and delicately phrased. While Nun Wand’re Maria arguably tests her vocal resources, Ummitternacht is eloquent and atmospheric, a fitting farewell by one of the last exponents of the nineteenth-century French grand vocal tradition.

© Vincent Giroud, 2015

Marston is fortunate to have André Tubeuf write a personal recollection of Germaine Lubin. M. Tubeuf has thoughtfully recorded his memories in this evocative essay in English.

Germaine Lubin

In late 1946, when I first came to Paris as a young student, the Opéra was at its lowest. But Germaine Lubin was news, making the headlines of both France Soir and Le Figaro. On trial in court, a tall figure, blonde, in furs, immensely dignified, she could have been Garbo facing accusation in Feyder’s silent film. Thus from the outset I knew her as the star she was. It was never given to me to watch her on stage, nor to see her in her rare later recital appearances in Paris. But from everywhere I was asking about opera, its history and legends, came the same words again and again: “You should have heard Lubin!” Together with Lifar’s her name was synonymous with beauty, nobility, music, and the twenty years when the Paris Opéra, as headed by the great man of theater Jacques Rouché, was a house dedicated to art, and art only. Then with the black years of Occupation and the resulting Épuration receding, the Paris Opéra sank ever lower. I had learned more about opera, by talking at length with the older ones. Quarrels were at long last put aside, and the time for sheer envy was past. Lubin had kept silent, since her banishment out of Paris — she did not appear in public places — one could again have kind words for her. And they were not only kind, they were rapturous: praising the sound and size of the voice, the quality, the overall noblesse, the unique stage intelligence. Former singers, composers, musicians all raved.

When in 1957 I settled in Strasbourg, a retired Germaine Hoerner was teaching in her native city: “Ah si vous aviez vu Germaine Lubin en Eva des Maîtres Chanteurs!” [Ah! If only you had seen Germaine Lubin as Eva in Die Meistersinger!] were her very first words when entering my home. With Hoerner it was our first real meeting — I had not so far even approached the other Germaine — Hoerner could not have known I admired Lubin from records, from photos, from what knowledgeable people had told me. She was just sharing the first example of beauty in opera that haunted her mind. Envy was gone. Admiration, gratitude indeed, alone remained. In the ten years we met weekly, Hoerner failed not once in this worshipping — like allegiance to a distant lost goddess. In the meantime I had been admitted into Lubin’s beautiful Quai Voltaire apartment in Paris as a frequent welcome visitor. At the time she was very, very lonely indeed. Her son Claude had taken his own life, by now History was past her, and Legend had not yet taken over. Only a handful of old-timers remained interested. I was much younger, by far, I was a teacher of philosophy, and did not approach her for small talk and compliments (though there were lots of them, and flowers as well). What I wanted was to understand: her artistic struggle, her fate; learn from her, have her speak in her own words, tell what it costs being the artist one is, keeping oneself up to singing such demanding music, bringing to life such devouring figures; dealing with Hofmannsthal, Strauss, Fauré; nothing regarding glamor, colleagues, or politics.

A book might and should have resulted. In the early 1960s Germaine gave me access to the incredible disorder of letters, photos, and even diaries kept in the drawers of the beautiful signed 18th century commode between her two windows facing the Louvre and the Seine (her boudoir and bedroom were completely furnished with the rarest, loveliest Charles X citronnier chairs and tables). Dozens of billets in Hoerner’s hand were there, testimony to years of friendly relationship. Never had they been stage rivals: Aida, Senta, or Chrysothemis were not Lubin’s roles, nor did Lubin mind the younger Hoerner taking Elsa or Sieglinde after her. Three times in those years Germaine asked me to take to Strasbourg a whole valise of letters and diaries to work upon; the idea of a book never was given up. The difficulty was that Lubin would not have a single date printed. She still looked a strikingly beautiful 50 years of age, blonde, with this incredible blue light in her eyes and across her face and that no less incredible bone structure. I remember making her wild-angry, quietly stating that then the reader might believe the war referred to was not 1914, but… 1870. She became far more flexible much later, more and more people showed interest in her, and she let Nicole Casanova publish her Isolde 39. I must have been the only one, however, who was actually permitted to read the letters and billets of people she no longer cared about or chose to forget, each time I took the valise I saw how much had vanished as in an autodafé. Even on photos she cut out people she would no longer see at her side, it happened even to Hofmannsthal sitting next to her one Ariadne evening in Vienna: she wished to remain with Strauss alone. Worst of all, month after month, she tore away pages and pages of what would have been a priceless cahier she had started writing in despair the day the father of Dominique had taken his daughter from her. It originally read, with interruptions, to the end of the war, her hiding weeks in a remote pension on Avenue Mozart when Paris was forbidden to her. Then, in dark loneliness, she had written of her consolation watching movies, warming and cheering herself up with Mario Lanza’s singing. There she wrote of her disillusion with the planned Tannhäuser in Geneva, when her voice did not respond; the hopes in Milan, when her friend De Sabata was unable to help, and had to do with Grob-Prandl as his Isolde. The next time I had the notebook in hand, entire pages were torn out, or heavy ink bars made specific lines or names impossible to read. Lubin’s true book, Lubin’s truth was never written, least of all, I hate to say, in interviews, of which she gave plenty, to visitors from France, abroad or overseas, once huge publicity had been made about her as teacher and hostess in Paris Presse (Henri Gault, of Gault et Millau fame, had been the ecstatic reporter). Max de Schauensee (he, at least, had known her glorious days) wrote of the gleaming blue light in Opera News. She herself from that moment on chose to show only the glamorous side of her past career, her everlasting beauty, the younger fans at her feet. Of the tragic fate Nemesis secures for those who by beauty, success, and pride, have trespassed the human limits, hardly ever a word (I can testify that fifteen years before, having her fate assimilated to Greek tragedy was her main concern). Filmed interviews exist where she looks not only radiant forever but somehow, it’s bitter to say, contented with herself, even fulfilled (which she never ever had been in her life, as a woman or as an artist). Here, along with her supremely beautiful spoken voice, dark hued, and her exquisite enunciation of the spoken word (in French or German or English), Lubin poses as a divinity, who triumphed over Jupiter’s thunder and even human (feminine) envy. For the few still alive who did know her — silent, thoughtful, deeply Christian, forgiving distress and loneliness — those famous and somehow notorious documents everyone can watch today on YouTube carry the gorgeous but totally wrong impression. As much as one really loving her will appreciate the fact that in these late interviews (now she was over eighty) at last she enjoyed recognition as the great artist and personality she had been, one has to say that Lubin in her glory and glamor conceals Lubin in her greatness. To this true Lubin, every form of enjoyment or satisfaction remained totally foreign. She just was the artist striving for unattainable perfection. Look not for the truth of Lubin the woman, she will elude you. Her truth forever and now has to be found in what remains of her voice on the records, frustrating as they may be, and in the photos, all so incredibly beautiful and proud, all showing what a lady she was. I have permitted myself to deal here above with the Hoerner case and such trifles as cut off photos and pages torn from a notebook. History (or memory, to start with) is no easy matter with singers, and Lubin, to be true, was exceedingly difficult. She had her standards, and that was that: therefore my inability to write the book she wanted from me. Dates and circumstances now no longer matter. What I learned from her and owe her, the truth and integrity of her uncompromising artistic drive and soul, may now be tentatively written, as a lifelong delayed tribute.

Lubin the lady

She was a grande dame in her unmistakable French way. Melba may have thought of herself as a lady because she dined with royalty, and a very young Farrar once took pride in bearing on stage jewels from the Krownprinz’s cassette. Lubin’s idea of behaving as a lady was that when singing Pénélope or Horizon chimérique, she did it the way Fauré wanted her to do, uplifting herself to the standards of someone she admired. Singing and acting Ariadne, she wanted to please Hofmannsthal, meet his own literary and artistic vision. Impersonating Isolde she was staring at, rather than Wagner (whom she did not think much of) the ideal Tristan she bore in mind, and spoke of as her life’s sole true love. As Elektra or Alceste she raised her gaze, cheeks, and arms to Sophocles himself, or to the gods of Greece. She never thought of pleasing herself, let alone those anonymous cheering hundreds which appeared to her through a cloud, — a mob. “La populace instruite,” as wrote Nietzsche describing Bayreuth, the ignorants and the knowledgeable put into the same bag. She met with her ideals late in the 1930s, during the famous Croisière Guillaume Budé which brought to Greece French artists from theater and music, academicians, and wealthy amateurs. Closest to her in soul and mind, she found Jacques Copeau, the foremost stage director in France, founder of the illustrious Vieux Colombier. They spoke of Homer, theater, and music; here was her world, from the start, dominated by Fate.

A beginner at the Opéra-Comique, it is not by chance that Lubin married Paul Géraldy, author of the best-selling Toi et Moi (his young wife was “toi”). First a most promising young poet, Géraldy soon grew to be an outstanding novelist and playwright, becoming close friends with Hofmannsthal. They translated each other for Vienna or Paris. Thus in the very early ‘20s, Lubin, not yet a star in Paris, found herself an acclaimed guest in Vienna, plum of their eyes to Berta Zuckerkandl’s coterie, which ruled over literary Vienna. There she talked (in perfect German) with Schnitzler and Max Reinhardt, and sang Ariadne under the baton of Strauss himself. With typical indirectness, Hofmannsthal found himself shy of his own words, while she was “the master of the language that contains all the others.” Every summer she spent two weeks with Lilli Lehmann at the Mozarteum, taking the disparaging remarks of the indefatigable teacher (“Dummes Kind” was the gentlest word), but hating being pinched. Until Lilli’s death they exchanged letters; one exists in which the older glorious singer bitterly complains that “bon goût” no longer exists, and that Art cannot survive democracy.

In Vienna she met Max Reinhardt who later would direct the Monte Carlo Rosenkavalier with her as Quinquin, delighted to discover her ability to enjoy and create fun on stage. Later he tried to cast her as Rosalinde in his Paris Fledermaus, which at that stage she could no longer dream of. But how sorry she felt, not working with him again! There she also became friends with Marie Gutheil-Schoder, easily the best acting talent in the whole Mahler ensemble, preparing her for her 1931 Salzburg Donna Anna, and Elektra, of which she had been the foremost exponent. With her Paris Elektra Lubin made the cover of L’Illustration, an unheardof event. Some complained one caught not enough of her words. They might have kept in mind that she sang the French translation, without the support of German consonants, which cut through the orchestra, and actually shorten the time of singing. Incidentally, as regards to enunciation: even we French find it difficult to understand Wagner as the Nuitters and Ernsts used to put him, with their very particular words, syntax, and prosody. Mind you, reading them we hardly understand! With the exception of “Mild und leise” with Gaubert, Erlkönig and a few Lieder, we have the Lubin recordings only in translation, with words both opaque in their meaning and uncomfortable to enunciate. Lubin was rather proud of her exquisite, soft but precise enunciation of the sung words, with their profound vowels. She saw herself as a successor to Racine’s Champmeslé, always aiming at the same nobility and poise French alexandrins should be given. She kept in her library splendid leatherbound Rameau and Gluck scores stamped with the royal armoiries. She had very much loved the idea (which came to no results) of Carl Dreyer watching her Alceste and dreaming of shooting a film with her. Dining with royalty was not her idea of being a lady.

When in Paris Lubin would socially meet with composers, writers, painters. The one fellow singer she talked and exchanged letters with was Claire Croiza, the very Croiza whom Paul Valéry worshipped (and wrote about) as the sovereign mistress of bien dire. But she was in warmest terms with a selected number of colleagues she respected, the tenor Franz and his wife first of all, Endrèze, Vanni-Marcoux, Journet (her admired Sachs), Pernet. Needless to say every day she fought with Jacques Rouché to get the best parts and a higher fee than he was disposed to grant her. He replied again and again, sweet as the gentleman (and mécène) but also very firm as the boss he was, that she was “le délicieux tourment de mon existence.” But he ended up agreeing. Who else was giving up so many foreign invitations to stay at his Opéra? Who else would learn and master, musically at the semi-quaver, in German or French (or both) the more strenuous Wagnerian parts, and Elektra, and Alceste, and Dukas’s Ariane, and Anna, all to be sung as repertory, anytime? Hardly could she find time or take pleasure in mundane life. But when she did show up in society, then Jeanne Lanvin or Mlle Alix (later Mme Grès) saw to it that she was the most exquisitely dressed woman — not the singer or actress she was, but the lady.

It may come as a surprise in the light of history still to come, but Lubin was ardently and proudly French. Though her career inevitably grew more and more German oriented, Alceste and Dukas’s Ariane remained to the end her two cherished parts, the two with which she found closest identification. Being the reigning queen at the Paris Opéra was enough for her; she was in no desire or need to try abroad. For ten seasons the Metropolitan wanted her, but she found no time or, to be true, interest. In Salzburg she was the first leading French singer invited, Anna in 1931 for Bruno Walter, receiving applause (one she was very proud of) from the Wiener Philharmoniker after “Non mi dir” and its virtuoso cabaletta (even more so when sung by an established Isolde). The same applause came from the Concertgebouw musicians after her Iphigénie (en Tauride) with Monteux. They hailed her as “another “Stradivarius.” She was ready to travel for concerts with first class orchestras and conductors as Walter, Weingartner, Furtwängler (whom Rouché invited for her), Beecham, von Hoesslin (very close to her heart and soul). De Sabata she knew from earlier Monte Carlo days when she sang for him Thaïs with Battistini and Aida and, most of all, Quinquin in the first French language Rosenkavalier. Having him in the Bayreuth pit (at every pianissimo he sent her a kiss; et il y avait beaucoup de pianissimos,” she added) with Max Lorenz as her Tristan was an unforgettable experience, the peak of her career. But she was happy enough at home with the orchestra led by Gaubert, Paul Paray, or even the lesser Szyfer or Fourestier. She never felt free to leave for a long period her home and daughter, whom she raised alone (quite daring, in those times, for someone so much in the public eye), holidaying in her Saint-Babel château in Auvergne, then at La Carte near the river Loire. Madrid she had visited very early in her career (Thaïs for King Alfonso XIII) Milan or Rome never, rarely even the French provinces where other foremost singers of the Opéra enjoyed fruitful invitations. Three times she turned down South America (Hoerner was happy to go in her place, first as Rameau’s Télaïre). When finally she could accept Alceste at New York (her daughter was no longer with her) France was already occupied, and she got no visa from the Germans (proof enough they did not trust her that much). Hers was an almost exclusively French career, except for festivals like Salzburg and Florence. Her first appearance in London was not really hers. As a gift from France for the Coronation, the Paris Opéra presented two seldom exported French works, Alceste and Ariane et Barbe-Bleue. There is a tale of Lubin’s nose bleeding forcing to delay the performance, Their Majesties having to wait. The truth is that since her daughter’s father was not her husband, British protocol would have nothing to do with him and a solution had to be found. After her personal triumph, she was invited back as herself in 1939, Kundry for Weingartner and Isolde for Beecham. There caught behind her like a shadow Mausi, the disturbed Friedelind Wagner, who fled Bayreuth and her imperious mother. She worshipped Lubin then (her passionate billets very early disappeared).

Lubin fought for parts, and would not let Mme Bourdon remain the leading Kundry in Paris. She also fought against parts. Having been Iphigénie (en Tauride) in concert, she would not play what she believed to be second fiddle as Clytemnestre (how mistaken she was) to the younger Iphigénie (en Aulide) even at Bruno Walter’s request. Her view of the importance of a part could be superficial indeed. La Sanseverina may be a duchess and by her sheer name bear magic, she definitely is second fiddle to Clelia Conti in la Chartreuse de Parme. No wonder she had to ask Sauguet for more music to sing, and lying higher up. First and foremost she saw herself as a proud high priestess of the French school, first Télaïre in Castor et Pollux (whom still very young she had shared with the great actress Françoise Rosay, then a singer) Alceste, Pénélope, the Arianes of both Dukas and Massenet, Salammbô, the creations of new works such as Maximilien and la Chartreuse de Parme in the ’30s, her former Antonia, Marguerite, Louise (praised to heavens by Charpentier) or Thaïs put aside long ago at that stage of her career. Italian operatic music she would hardly touch: Aida very early, Tosca very late, neither heroine being the average “petite femme,” loving and tearful, whom Lubin hated —even Sieglinde she despised as in her own words “une vaincue.” A victim she would be, but enthusiastically, of her own will — a heroic one.

Towards Wagner she went one step after the other, perhaps with a foreboding that her Fatum lay there, and anxious that it should not strike too soon. She dared not take Isolde from one of Rouché’s modest Wagnerian ladies, and tried discreetly in Nantes, and in Italian at that, with Amedeo Bassi (Bassi’s enthusiastic letters disappeared early from Lubin’s drawers: obliteration was that first Tristan’s fate). Only in the early ’30s after her first Götterdämmerung Brünnhilde and first Kundry did she become (though the Paris Annas were still to come) more and more attracted to German ecstatic singing. She would be fifty in 1940, still the supreme sostenuto (and pianissimo) singer, along with Flagstad and the darker Frida Leider. On stage she would soon be somehow condemned to the more heroic Wagner. That was Fatum. Still, the words she most gladly inscribed on her larger photographs she quoted from Maeterlinck’s Ariane, and they are testimony to what she thought exactly of herself as a bold, battling heroine in life and in song : “C’est la passion de la clarté qui a tout pénétré, ne se repose pas, et n’a plus rien à vaincre qu’elle-même.” (“The essence of that passion of the light which hath pierced through all darkness, which knows no repose, and has henceforth itself only to conquer!”)

With France at war, then defeated, never would she accept to sing in Germany, though Bayreuth insisted that she come back as Brünnhilde in the Ring. She was too French at heart and in her blood. But at the same time she was Lubin the queen and did not object to privileges others could not dream of in occupied Paris: her car and gas for it, the brand new white telephone for which she claimed very very high in the German hierarchy. Ideally blonde with that blue light in the eyes, the Führer had been at her feet in Bayreuth (though pictures show her quite ostensibly always turning her head from him). She begged indeed, and loud and persistently, for her son Claude, in poor health, a prisoner in a war camp. He was set free indeed. And so was Marya Freund, whom she rescued from Drancy, who emphatically wrote she kissed the beautiful hands which, as in Fidelio, open the gates of prisons. When in May 1941 the Berlin Opera came in a special train to present Entführung and Tristan in Paris, the whole Bayreuth ’39 cast was reunited, the French Isolde joining her German colleagues (and Karajan taking over from De Sabata). She felt it was her duty to assert in this time and place that there existed still a challenging, proud strength of French art against so many humiliations. Many felt the same way, best of all Jean Cocteau who wrote to thank her for an evening which had restored his “forces profondes.” Needless to say, by many others this very same evening would be deeply resented and the day came when she would have to pay an enormous penalty for it. When the thunder struck in August 1944, the scandal for her was not being crushed to the ground, but this mob setting hands on her, the sordid materiality of it. Was it a surprise? For years she had been assuming in her parts more and more, as an artist, the place of the glorious and miserable sacrificed one. Now her own theater was coming true. Her first night in jail (so she repeatedly said), looking to the empty and silent night, she heard the sound of a flute from another cell playing the tune from the William Tell overture, and discovered there is a mysterious communication from mind to mind, and to the Universe, which reveals itself only to the outcast and outraged ones. Then came weeks, months, years indeed of repeated trials and national indignity which she endured throughout, shut in her pride. Never a single moment did she feel herself guilty of anything else than being and remaining herself: the very same thing for which she had first been worshipped. No more, no less. That is pride indeed, along with some quite extraordinary kind of Christian humility, quite beyond average understanding. So she was, and would stay.

Later on she was very keen to teach. Her so-called indignity barred her from a position at the Conservatoire, which would become the poorer for it. She had something to transmit. She was immensely aware that the best had been given to her through natural gifts and by her teachers, and she had to pass it on in turn. Until Litvinne’s death Lubin took loving care of the impoverished great artist whose voice as Alceste resounded in her mind as the liquid golden mellow fire that her own voice had to become. And she never forgot the very moment where Litvinne taught her how to lighten her tone, in order to move freely higher and higher up in the arioso. From “la grande Lilli” (as Reynaldo Hahn always named her) she had to pass on the spirit of perfection, harder and harder (pinching or not). To that mission, she gave herself whenever she found in a pupil the requisite talent and character —Rachel Yakar being the one she cherished and built up from beginning to end. Is it believable? Artist as she was, to her bones and somehow, as Isolde, herself a Todgeweihte, born to death in art, yet at the same moment she, Lubin, remained basically natural, healthy, unaffected. I found her on a Sunday morning playing a Leo Ferré record again and again, marveling at his “mmm’s” in “Paname” and “Jolie Môme” and would have a pupil now trying them in Wagner. On her piano she always kept her Tristan score and Debussy’s Promenoir des deux amants, along with Strauss’s framed picture inscribed to his Daphné and Marie to be (that had been the dream; both on the same evening, with her and her only: she would not leave much to the envious ones.) But she needed no score, her memory was enough one evening, when darkness insensibly crept into the beautiful Quai Voltaire salon. She let her fingers quietly, almost silently, move over the keys and together she sang, no, she spoke in that musical deep voice of hers, Ariadne’s “Es gibt ein Reich…” Yes, there is a kingdom… You cannot believe how radiant and bright that fabled blue light in her eyes then was…

© André Tubeuf, 2015

Lucienne de Méo

Lucienne de Méo (whose name has incorrectly been sometimes listed as Cléontine) was born in Paris on 17 March 1904. Initially trained as a violinist, she took up singing at the Paris Conservatory, studying with Thomas Salignac and Émile Engel, and was awarded first prizes in singing, opera, and opéra-comique in 1927 after being heard as Alceste, Rezia, and as Manoutchka in Alfred Bachelet’s Quand la cloche sonnera. Louis Schneider noted that her voice was “of the most solid metal, it is ample, sonorous, well led” and predicted she would “rise above the orchestra.” After appearing in concert that summer, she made her Paris Opéra debut in November as Sieglinde, along with Paul Franz as Siegmund, Marcel Journet as Wotan, Jeanne Cros as Brünnhilde, and Ketty Lapeyrette as Fricka, with François Ruhlmann conducting. (Jeanne Bourdon sang Brünnhilde in subsequent performances.) In the same month she took part in the inaugural concert at the brand-new Salle Pleyel, singing Isolde’s Liebestod and Alceste. “She possesses undeniable gifts,” wrote Raymond Balliman in Lyrica: “...focus, intelligence. Her voice, of adequate quality, is placed slightly backward; for the time being, it lacks the breadth of a dramatic soprano. Her declamation is exact and forthright; despite her efforts, her articulation is defective and confused at times; her r’s are at times rolled, at times soft [grasseyés, which was normally proscribed in good singing], which induces a contraction that moves the sound to the following syllable.” He advised her to be prudent in her choice of repertory and stay away from heavy roles. Nevertheless, in February 1928, in concert, she sang Brünnhilde in the final scene of The Walkyrie, with Hector Dufranne as Wotan, and later that year, also in concert, she sang the final scene of Götterdämmerung. At the Opéra she was heard as Marguerite in Faust, with Edmond Rambaud as Faust and Jean Claverie as Mephistopheles, under Henri Busser, and as Alceste, with Georges Thill as Admète, in the spring; and in the summer as Octavian, with Charlotte Tirard as the Marschallin, Marthe Nespoulos as Sophie, and Albert Huberty as Ochs, under Gabriel Grovlez. She made an unscheduled first appearance as Donna Anna in May, stepping in for an undisposed Maria Nemeth when the Vienna Opera appeared on tour. Her partners included Hans Duhan in the title-role, Richard Tauber as Ottavio, Elisabeth Schumann as Zerlina, and Richard Mayr as Leporello; Franz Schalk was conducting. “She acquitted herself of her difficult task,” Reynaldo Hahn wrote in Le Journal, “with a bravura and rhythmic assurance infinitely laudable in such a young singer who, only a few months ago, was a student in the Paris Conservatoire.” In the same year she also appeared at the Opéra de Monte-Carlo, in February, as Marguerite in La Damnation de Faust, with Franz Kaisin as Faust and Étienne Billot as Mephistopheles, under Victor De Sabata. In 1929, while continuing to sing her previous roles at the Opéra, where she also appeared as a Flower Maiden in Parsifal and as Elsa (alongside Sullivan’s Lohengrin), she partnered Franz as Sieglinde in Toulouse and sang a highly successful Tosca in Algiers in February, with tenor François Darmel as Cavaradossi and baritone Feiner as Scarpia. In Lille, she sang the Berlioz Marguerite, with José de Trévi as Faust and André Pernet as Mephistopheles, and also appeared as Elisabeth in Tannhäuser in Lille, with de Trévi in the title-role, Georgette Caro as Venus, Louis Guenot as Wolfram, and Fred Bordon as the Landgrave. In 1930 she sang Salomé in Hériodade in Besançon and Sieglinde as part of a complete French-language Ring at Strasbourg. She was apparently preparing to sing Desdemona at the Opéra when, suffering from depression, she committed suicide in June of that year—though her death was reported in the press as resulting from a sudden illness.

De Méo’s three recorded sides are a tantalizing testimony to a tragically interrupted career that could have reached great heights. They reveal an attractive, clear soprano voice, evenly produced, capable of sweetness and soft attacks (as in Agathe’s “Und ob die Wolke”), with a powerful top (as in Alceste’s “Divinités du Styx”) and an eloquent delivery (as in “Die Männer sippe”). In all three instances her enunciation is excellent. There is no evidence that she appeared in Der Freischütz on stage, but she probably worked on the part at the Conservatoire, where Alceste was among her competition numbers. As Sieglinde, her debut role and the one she remains especially associated with, she is inclined at times, like other great exponents of the part (Leonie Rysanek, for one), to sing enthusiastically sharp. This may explain why this Columbia test recording was not released.

© Vincent Giroud, 2015